Safety of Research Chemistry Laboratory Chapter 5

Date: 2022-01-19 Source: RUANQI Classification: Resources

#This series is translated from the safety guidance book on research chemistry laboratory printed by the chemical safety committee of the Joint Council of American Chemical Societies. It is the best practical guide for freshmen and sophomores#

Chapter V safety equipment and emergency response

Introduction

Although the laboratory is a place for learning and skill development, it is important to be prepared for appropriate response to accidents reaction. Accidents can occur even if recognized hazards are properly managed. In an academic environment, the instructor's responsibility for events is certainly greater than that of students, but the purpose of this chapter is to help you prepare for accidents as a student and later as a scientist. With this in mind, always follow the guidance of your mentor and the policies of your organization.

In the previous chapters, you have learned the first three principles of ramp: identifying hazards, assessing the risk of hazards, and minimizing the risk of hazards. The first three principles of ramp will reduce accidents and help avoid emergencies, but they may not be completely prevented. The fourth part of ramp is emergency preparedness.

This chapter includes how to prevent accidents and prepare for accidents. If you spend some energy thinking about potential events and your response, you are more likely to remain calm and respond appropriately to emergencies. The most common emergencies you may need to deal with in a junior laboratory include spills, fires, cuts or burns.

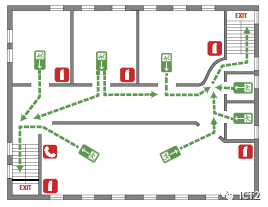

Schematic diagram of evacuation route

When you begin to think about how to deal with an emergency, when you first enter the laboratory, take a moment to look around and identify safety equipment, signs, fire alarms and exits. Items you can find include fire extinguishers, safety showers, eye wash stations, evacuation signs, emergency gas shut-off devices (if possible), first aid kits and fire blankets. If your laboratory is equipped with each of the above items, pay attention to those closest to you. Some safety equipment, such as fire extinguishers and eyewash stations, will be tested regularly and will have a label with the date of the test. Although it is not your responsibility to check this safety equipment, if you find that any equipment is overdue or access is blocked, please inform your instructor.

Your mentor is probably the first person to respond to a laboratory accident. However, your teacher may leave temporarily, work with another student, or be far away from the event, and you need to respond quickly. When preparing for an emergency, remember that the primary goal is to protect life and reduce injury. Never put yourself in danger. The second objective is to minimize damage to buildings or equipment. You should follow the emergency procedures established by the school under the guidance of your tutor.

In some cases, you may be the only person who can respond to an accident. Before you try to help others, assess the current situation and the potential risks to yourself. If you get hurt in the process, you can't help others. In general, the emergency procedures you may need to follow will depend on the type of direct danger and injury suffered, but may include components of the following steps.

Determine if you and others need to leave the area immediately, or if there are things you can do safely to minimize injury and damage (see later chapters).

• report the nature and location of the emergency to your instructor or call 911 (or your organization's emergency number) if necessary to contact the appropriate fire or medical assistance. Be prepared to answer the dispatcher's questions, such as your name, location and the nature of the event. It may be necessary to send someone to pick up an ambulance or fire brigade at the entrance of the building, as these people may not be familiar with your building.

• inform others in the area of the nature of the emergency and call the campus security office.

• do not move injured persons unless they are in immediate danger of exposure to chemicals or fire. Keep them warm. Unnecessary activities can seriously complicate neck injuries and fractures.

■ flammable or combustible

These words are often used interchangeably in daily conversation. Many dictionaries use these terms to define each other. The following is typical (but not very useful): "flammable; flammable."

When these terms are used to describe the fire risk of organic solvents, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the global harmonized system of chemical classification and labelling (GHS) use two standards that affect the fire risk when solvents are used: ignition point and boiling point. The ignition point of volatile solvents is the lowest temperature at which enough steam is released from the liquid surface to form a combustible mixture with air.

Unfortunately, NFPA and GHS have slightly different definitions of "combustible" and "flammable", but the general difference is that combustible liquid magnesite burns at room temperature, while combustible liquid burns at high temperature. Combustible liquids are usually dangerous in the laboratory. When the fire source is removed, the combustible liquid may or may not continue to burn.

In NFPA and GHS systems, there are additional standards for defining these terms for gases and solids. In all cases, combustible and flammable substances will increase the fuel of fire, and appropriate precautions must be taken in the laboratory.

Fires

Fire prevention

The best way to put out a fire is to prevent it. Think about the fire protection principle of ramp.

• is any heat source, flame or spark used?

• are flammable liquids or vapors used?

• are there any damaged wires on the electrical equipment?

• are bottles or glassware (including flammable solvents) too close to the test bench?

• is the work area messy?

When using flammable liquid, please try to reduce the amount of reagent in the workspace, only allocate the amount required by the experimental procedure, and put the reagent bottle back to the appropriate storage location immediately after distributing the materials. Excess flammable materials in the immediate work area will act as an additional source of fuel in a fire. You should also keep combustible materials, such as paper, away from places where combustible chemical experiments are being carried out.

In case of fire, combustible materials will also be used as fuel to keep the fire burning. Do not store flammable materials on flammable cabinets.

When heating flammable solvents, it is important to avoid the presence of fire sources. Open flames should not be used to heat flammable solvents. The electric heating plate is relatively safe, but small sparks are often generated when electrical equipment is switched on and off. If there is enough steam in the solvent, the spark will cause a fire. Some electrical equipment is designed to be "intrinsically safe", which means that it has a design to prevent such sparks, but this is not common in most laboratories. Therefore, when heating the solvent, it is very important to avoid the possible combustible gas, which is usually required to be carried out in the fume hood. If any electrical equipment has sparks or wires are worn, turn it off immediately and inform your tutor.

Good sorting habits are of great help to prevent accidents and reduce the impact of accidents. Although the teacher's main responsibility is to regularly check the wires on the equipment and ensure that the channels and exits are unblocked, it is a good habit for you to learn to observe the "Scene" or area. Even if the risk is well managed, an emergency may still occur in an academic laboratory with many students present. Maybe you're dealing with a situation you didn't cause.

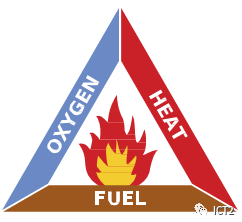

Preparation for fire

The three components of the fire triangle: heat, fuel (flammable or combustible materials) and oxygen (or other oxidants). The beginning and continuation of fire must have these three elements. Removing one of these elements will prevent or extinguish the fire.

If there is an accidental fire, your quick response can prevent a small accident from becoming a big accident. You need to decide whether to put out the fire or escape to a safe place, but you must follow the guidance of your mentor. If you decide to put out the fire, be confident that your actions will not expand the fire or put yourself or others in a more dangerous situation. It is best for your organization to conduct its own fire training as part of the safety training related to the laboratory. If so, you and your classmates should know what to do in case of fire emergency and follow these guidelines.

Do not pick up containers or equipment that are on fire. Sprinkling water on certain types of fires may spread the fire. The best way to put out a small fire in the laboratory is to smother it. The following steps should only be considered if you are confident that you can safely take the following steps when preparing for an emergency fire.

• remove the heat source by turning off the gas supply to the Bunsen burner or unplugging the electric heater.

• fires in small containers can usually be extinguished by limiting air / oxygen. For example, a fire in a small beaker or Erlenmeyer flask can be extinguished by using non combustible items, such as glass on a clamp or the flat bottom of a large beaker.

• do not cover the fire with dry towels or dry cloth because they will add fuel to the combustion. If so, you can use moist materials. In order to avoid the spread of the fire, the nearby inflammables must be removed under safe conditions.

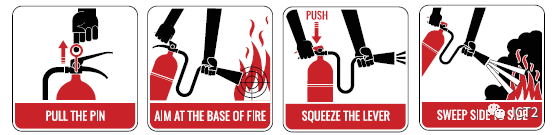

• if the steps listed above are not practical or do not extinguish the fire, a fire extinguisher may be used to extinguish the fire. If you have received training in using fire extinguishers or are otherwise confident in using fire extinguishers, put yourself between the fire and escape routes (such as doors) and put out the fire from this position to ensure that you can escape. Small fires can often be put out, but not always. It's easy to underestimate fire. If not put out, the fire will soon threaten your life.

If the fire occurs in an area that is too large to put out the fire quickly and simply, everyone should evacuate the area. Pull down the fire alarm and evacuate according to the evacuation procedures specified by your organization. Once you are safe, make sure you or someone else calls 911 (or your organization's emergency number) to notify the appropriate emergency assistance. Although it is difficult to know who is in the building when the fire occurs, it is important to find other students and teachers outside the building and let them know that you are safe. If you have the ability, help those who are unable to move.

Preparation for personal injury in fire

If someone's clothes catch fire, it will be a terrible situation. He may instinctively run away. Running away makes the situation worse because it will fan the flame, and the heat and gas generated by the combustion are likely to be inhaled by people standing, walking or running. Firmly tell the man to stop, fall and roll over. This may extinguish the flame. You can put out a small burning fire with a towel or jacket. Let the person lie down and stretch down to his feet. These recommendations follow the procedures established by the National Fire Protection Association(NFPA), which assume that a person is in a common non laboratory environment. Another option in the laboratory is to place the patient under a safe shower or, if convenient, flush it with a flushing hose in the laboratory sink. You must judge the best way you can help.

Never wrap a person standing with a fire blanket, because it will spray flames and toxic gases directly to the face. This is the so-called chimney effect. When a person is in the shower, the fire blanket can be used as a movable curtain to keep the injured warm, as a cushion, as a shawl when no emergency clothes are available, or as a stretcher. If your unit has a fire blanket, you should use it according to the local instructions. Call 911 (or your organization's emergency number) to get medical help quickly. Covering the victim with a blanket or jacket helps to avoid shock and exposure.

Chemical contamination of skin, clothing and eyes

Prevent chemical contact

Exposure to chemicals may be due to accidental skin contact, splashing and spillage. Leakage and how to prevent and respond to leakage will be discussed below. Chapter 2 includes practical rules for the laboratory to help you avoid chemical contact, including various forms of personal protective equipment (PPE). You may want to review these practical rules to prevent accidents.

Preparation for chemical exposure

Again, your teacher may help you or other students when something happens. The suggestions given here are general and will help you know how to deal with events.

For spills or splashes that affect only a small part of the skin, you should immediately flush the skin with running water for at least 15 minutes (30 minute basis). You should remove any jewelry to facilitate the removal of liquid that may remain between the skin and jewelry. This is one of the reasons why you are advised not to wear jewelry in the laboratory. After the first rinse with water, wash the entire area of infected skin with warm water and soap. You or your classmates should inform your tutor as soon as possible. After cleaning the skin, check the safety data sheet (SDS) to see if there will be any delay. Seek medical care even for minor chemical burns. Many organizations will ask you to fill out a short initial injury notification form. This protects you from complications due to exposure to the laboratory.

If you spill solid chemicals on your skin, it is recommended to brush them off before using water. Credit cards are very useful in this process Brushing off corrosive solids usually has no adverse consequences, and exposure can actually be reduced by avoiding the temperature rise caused by solution exothermic heat, which is common when adding water. When these substances are brushed off your skin, wash your skin with soap and water and tell your mentor about it.

Of course, the brushed solid should be placed in a suitable waste container, not in a sink or ordinary dustbin. In case of contact with acid, do not apply neutralizing chemicals (such as sodium bicarbonate) to the skin. Neutralization produces heat that increases damage.

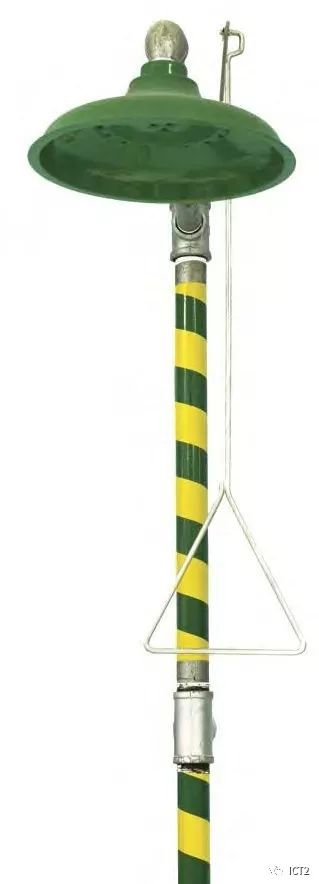

If the skin or clothing is contaminated with a large amount of liquid, there may be more serious consequences. You should immediately go to the nearest safety shower, turn on the water, and quickly step on the water spray. Some showers will remain on until they are turned off, but others will require the hand to be placed in the "on" position to maintain water flow. When you are in flowing water, take off all contaminated clothes, shoes and jewelry. Every minute counts. Don't waste time. Delays due to modesty can turn contact into serious injury. When asking others to cut off pullovers or sweaters with scissors, avoid soiling your eyes and face. You should rinse the affected area with water for at least 15 minutes, but if the pain recurs, rinse the affected area with water again. Your mentor is unlikely to be unaware of the need to use a safety shower, but inform your mentor as soon as possible. After rinsing thoroughly with water, seek medical attention. If possible, your teacher will take SDS to the medical institution, but you may be helpful in identifying the names of chemicals. Many organizations will have extra clothes (such as sweatshirts and pants, or hospital overalls) to replace your contaminated clothes immediately. As described in Chapter 2, contaminated clothing should be washed separately from other clothing or discarded according to the recommendations of SDS.

If your eyes are splashed with chemicals, you should race against the clock and quickly go to the nearest eye washing station to wash your eyes for at least 15 minutes (based on 30 minutes). You should use your thumb and index finger to remove the eyelids from your eyes, move your eyes up, down, left and right, and flush the area behind your eyelids. If you are helping people who have been splashed with chemicals in their eyes, you may need to take them to an eye wash station. It is worth reiterating here that wearing chemical splash goggles will fundamentally eliminate the possibility of such events.

If there is no eyewash, use the nearest flowing water source and keep the water as close to room temperature as possible. Alternatively, you can help the injured person lie down on his back and gently pour water into the corners of his eyes for at least 15 minutes. If possible, remove your contact lenses. You should inform your instructor as soon as possible. After rinsing the injured eye, seek medical attention. If possible, identify chemical contaminants so that your teacher can bring an SDS to the medical institution.

Note: Although current best practices require warm water from eye wash nozzles and safety showers, this may not apply everywhere. If the exposed person starts to tremble or complain that it is too cold, have the best judgment on the cleaning time. Do not let people exposed to chemicals have hypothermia.

■ extension: HF exposure treatment

As described in Chapter 3, the hazard of hydrofluoric acid (HF) makes its use very dangerous. HF exposure is extremely dangerous and requires special treatment; When using hydrogen fluoride, calcium gluconate gel or cream should be prepared at any time. If the skin is contaminated by HF, you should use this gel and seek medical attention immediately. Hydrofluoric acid cannot be used without special training and supervision.

Other Personal Injury

Prevent other personal injury

Other types of personal injuries include slips, trips, falls, electric shocks, chemical ingestion, inhalation and cuts. Refer to the general rules in Chapter 2 and the use of chemical fume hoods and electrical equipment in Chapter 4 to avoid these accidents.

Preparation for other personal injuries

Although fires and spills are the most common types of accidents in the laboratory, consideration should be given to how to deal with other possible situations, including chemical inhalation, chemical ingestion, electric shock and cuts.

If you or others in the laboratory are troubled by smoke, steam or smoke, please move yourself and others from the area to fresh air. You should warn others in the area of possible injuries and seek medical assistance immediately. If you suspect that someone has ingested hazardous chemicals, call 911 (or your organization's emergency number) and follow the first aid treatment shown on the label or SDS. You may assist your mentor in first aid. Don't give anything to an unconscious person. Your instructor will ensure that the medical institution has a copy of the SDS, but you may need to determine which chemicals are involved.

You shouldn't meet people who touch live circuits. You must disconnect the circuit by unplugging the equipment or closing the circuit breaker, otherwise you will also receive electric shock.

If the injured person is not breathing and has no pulse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be provided if you have been trained, or automatic external defibrillator (AED) should be used if available. You should call 911 (or your organization's emergency number) immediately or tell others to do so while you look after the victim. Since there may be several people present in the academic laboratory, it is best to have one person call 911 and the other find the laboratory instructor or other authority to call campus security and assist CPR.

If you or someone else is bleeding badly, try to control the bleeding by putting a cloth on the wound and applying pressure. If possible, raise the injured area above the heart level. You should take reasonable precautions to avoid contact with other people's blood. Most chemical laboratories have gloves. In addition to minor wounds, wrap the injured person in a blanket or coat to avoid shock and seek medical attention immediately. Do not clean up biological leaks that may contain blood borne pathogens unless trained.

Chemical Spills

Prevent chemical leakage

Chemical spills are probably the most common laboratory accidents. Good housekeeping habits will help you avoid chemical spills. Keep laboratory items away from the edge of the laboratory bench or other workspace. You should measure the amount of chemicals according to laboratory procedures and avoid excessive intake of chemicals. Once the minimum amount required for the experiment is obtained, return the reagent bottle to the appropriate position. If you observe obstacles in the aisle or walkway of the laboratory space, please inform your teacher. Walk slowly and carefully in the laboratory. Haste may cause you to run into other students or cabinets and other laboratory furniture.

If you have to transport samples or solutions from one part of the laboratory to another, support the beaker or flask under the container with one hand. Remind others if necessary. Transportation of chemicals from the laboratory to the instrument or storage area requires secondary sealing with rubber buckets or plastic bags.

Preparation for chemical leakage

If a chemical spill occurs to you or to people near your workplace, you and other students in the area should stay away from the spill. If flammable liquids spill, warn other students in the area to extinguish all flames and turn off electrical equipment. If you do so, you will not hurt yourself. If the leak occurs in the chemical fume hood, close the fume hood window frame to remove the steam more effectively. You should report the leak to your teacher immediately. Your teacher should know how to deal with the leak. If a large amount of flammable, toxic or volatile substances are spilled, it may be necessary to vacate the whole laboratory or building.

If a small amount of solid material leaks, your teacher may instruct you or others to use dustpans and brushes usually stored in the laboratory to clean the material. If a small amount of liquid material leaks, your teacher may instruct you or others to absorb the liquid with a paper towel or other absorbent. To pick up broken glass, use pliers or leather or cut resistant gloves. You can also clean broken glasses with a small brush and dustpan. Most likely, the teacher will clean the broken glass, or you may be asked to do so under close supervision. Dispose of materials, including paper towels, as directed by the teacher.

If a large number of substances are leaked, or the materials are toxic or flammable, your organization will have formal procedures to deal with the leakage. Follow the instructions given by the teacher. These leaks were not handled by students in the introductory laboratory.

Your teacher or other trained personnel may use absorbent retention materials on the floor to surround large liquid spills. The absorbing material used can be a material that neutralizes the overflow material (limestone or sodium carbonate for acid, sodium thiosulfate solution for bromine, etc.). There are commercially available absorbent kits (e.g., oil DRI and zorb all), but other readily available absorbers, such as vermiculite or clay based cat litter with small particles (about 30 mesh), can also be used effectively. When you are instructed to return to the area, make sure that the floor does not make you feel slippery. Let the coach know if the area is unsafe for any reason.

■ chemical leakage - slight or large

To determine whether you are qualified to clean up spills, you need to know the variables. Consider the following

Minor or simple leakage:

• leaks that can be managed by one person

• spills that do not spread rapidly except in direct contact

• leakage will not cause direct harm to the environment

• workers understand hazards (physical, health and environment) (toxicity, flammability, corrosivity and reactivity)

• provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and leak proof kits

Major or complex leakage:

• leakage also involves injury

• spilled highly toxic or flammable substances require immediate evacuation of the area

• spillage from stairwells or other high-altitude areas

• spillage accidents have a serious impact on the environment

Summary

The most likely emergencies that may occur in introductory or organic chemistry laboratories are ignition of flammable solvents, exposure to chemicals in the skin or eyes, cutting of broken glassware, and chemical leakage. If you have considered your answer in advance, you are more likely to respond appropriately to minimize injury and damage.

Learning to work safely in the laboratory is an important part of undergraduate chemistry education. Recognizing hazards and assessing and minimizing risks are habits that should continue to develop throughout education and career. This chapter describes how to prevent accidents or leaks. Preventive education is important, but preparing to respond in an emergency is equally important and should be part of your education.